1. See, for example, Emmanuel Macron, “Dear Europe, Brexit Is a Lesson for All of Us: It’s Time for Renewal,” Guardian, March 4, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/mar/04/europe-brexit-uk.

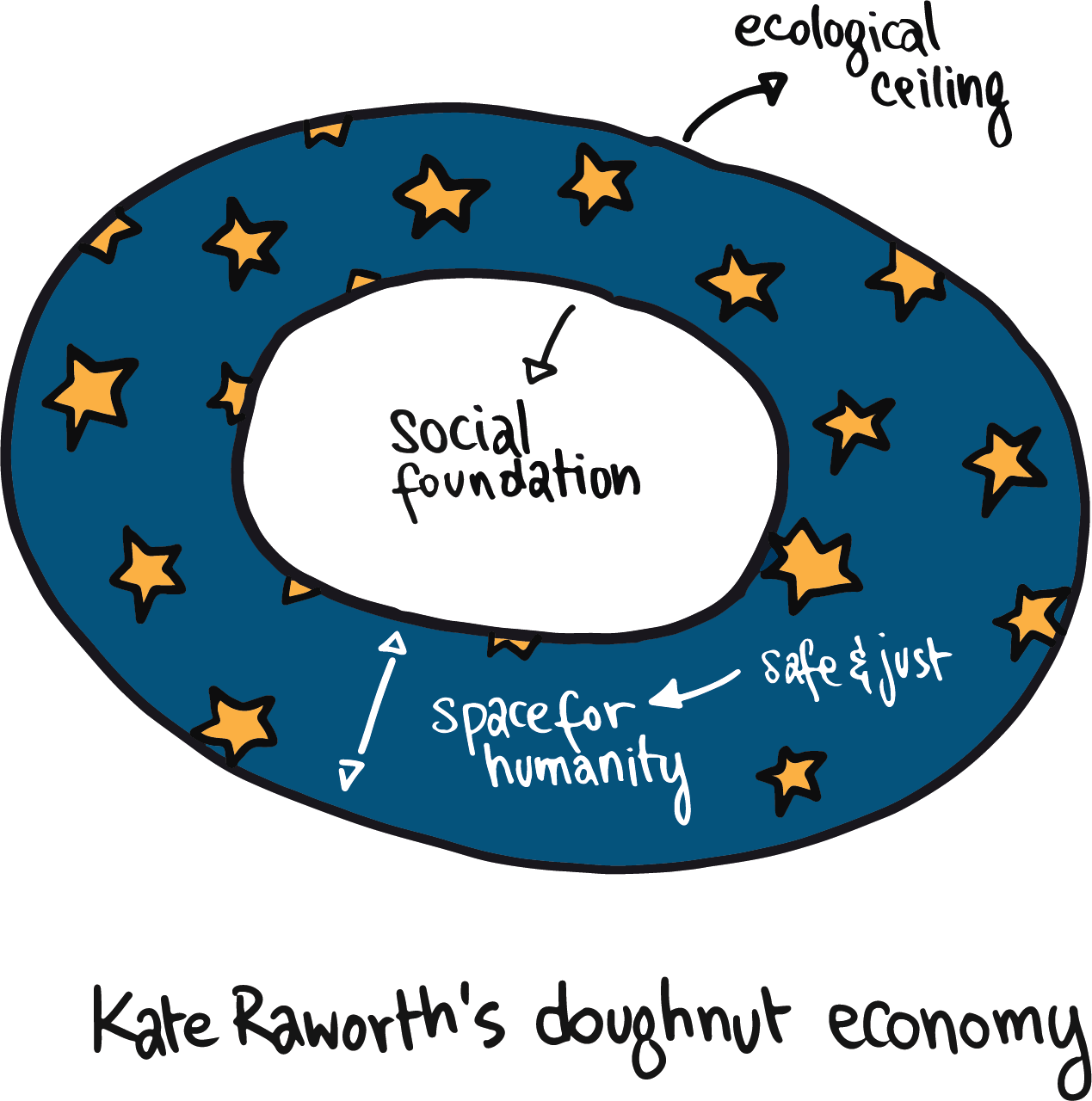

2. Kate Raworth, “Exploring Doughnut Economics,” https://www.kateraworth.com/doughnut/.

3. The illustration, as noted in the text, is inspired by Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economy diagram. The original diagram is available here: https://www.kateraworth.com/doughnut/.

4. The EU Needs a Stability and Wellbeing Pact, Not More Growth,” Guardian, September 16, 2018 (https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/sep/16/the-eu-needs-a-stability-and-wellbeing-pact-not-more-growth

). The letter was published in eighteen European languages in the run up to the Post-Growth 2018 Conference, hosted in Brussels on September 18–19, 2018, by ten members of the European Parliament from five different political groups, alongside trade unions and nongovernmental organizations, https://www.postgrowth2018.eu/.

5. See, for example, the work of Ottmar Edenhofer, director of Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, https://www.pik-potsdam.de/members/edenh.

6. An example of this type of work is provided by Janette Sadiq-Khan, a former commissioner of the New York City Department of Transportation. See her book, Streetfight: Handbook for an Urban Revolution (New York: Penguin Books, 2017).

7. The European Commission projects that the EU population will grow by 1.7 percent between January 1, 2016, and January 1, 2080 (see European Commission, People in the EU—Population Projections, December 2017, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/People_in_the_EU_-_population_projections). This increase is only due to immigration. There are differences between member states: “decline in the number of inhabitants is projected to be within the range of 11-13 % in Italy, Hungary, Slovakia and Estonia, while reductions of 22-27 % are projected for Croatia, Poland, Romania and Portugal. Larger contractions — with the total number of inhabitants falling by approximately one third — are projected for Greece, Latvia and Bulgaria, while the largest reduction of all is projected in Lithuania, as its population is predicted to fall by 42.6 % between 2016 and 2080.” The median age is projected to increase by 4.2 years between 2015 and 2080 to 46.6. Europe’s population will fall behind significantly in comparison to Africa and Asia (see European Environment Agency, Population Trends 1950–2100: Globally and Within Europe,” October 2016, https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/indicators/total-population-outlook-from-unstat-3/assessment-1).

8. 2018 Ageing Report: Policy Challenges for Ageing Societies,” European Commission, May 25, 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/info/news/economy-finance/policy-implications-ageing-examined-new-report-2018-may-25_en.

9. Kontis et al., “Future Life Expectancy in 35 Industrialised Countries: Projections with a Bayesian Model Ensemble,” Lancet<389>(2017): 1323–35, https://www.thelancet.com/action/showPdf?pii=S0140-6736%2816%2932381-9.

10. A lack of opportunity at home and the lure of Western Europe—made accessible by EU membership—has resulted in millions leaving Central and Eastern Europe (see European Commission, People in the EU— Population Projections).

11. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) found that approximately 14.7 percent of jobs could be lost to automation and that it may be difficult to retrain many of the people who lose their jobs. Most jobs likely to be lost are those that require little or no education (see Ljubica Nedelkoska and Glenda Quintini, “Automation, Skills Use and Training,” Social, Employment, and Migration Working Papers, OECD, March 8, 2018, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/fr/employment/automation-skills-use-and-training_2e2f4eea-en). The World Economic Forum argues that robots will replace 75 million jobs globally but also create 133 million new ones (see “WEF: Robots ‘Will Create More Jobs Than They Displace’,” BBC News, September 17, 2018,https://www.bbc.com/news/business-45545228).

12. By reducing the number of low-skilled jobs, automation creates a divide between the educated and uneducated. This is already evident in voting patterns and political attitudes across Europe (see the “diploma democracy” argument by Mark Bovens and Anchrit Wille, “It’s Education, Stupid: How Globalisation Has Made Education the New Political Cleavage in Europe,” London School of Economics and Political Science, July 2017, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2017/07/05/its-education-stupid-how-globalisation-has-made-education-the-new-political-cleavage-in-europe/).

13. Szymon Górka, Wojciech Hardy, Roma Keister, and Piotr Lewandowski, “Tasks and Skills in European Labour Markets,” Instytut Badań Strukturalnych, May 2017,

http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/303651521211509917/Tasks-and-Skills-in-European-Labor-Markets.pdf.

14. The problem is that EU member countries are facing a large foundational skills gap. Across half of the EU, a fifth or more of 15-year-olds performed below the proficiency level in reading and mathematics in the Program for International Student Assessment. A large segment of young people all over the EU lack the necessary skills to do cognitive and nonroutine tasks, which will be even more important in the future labor market (see European Commission, Eurostat, “Underachievement in Reading, Maths or Science,” 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=sdg_04_40&plugin=1).

15. European Parliament Press Release, “European Fund for Transition to Support More Workers Made Redundant,” January 16, 2019, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20190109IPR23022/european-fund-for-transition-to-support-more-workers-made-redundant.

16. International standard-setting organizations, such as the International Labor Organization (ILO), should try to get consensus around new global standards for the digital field of work. See, for example, the latest report from the ILO Global Commission on the future of work, which strongly recommends that all relevant organizations in the multilateral system work together toward setting standards (see ILO, Global Commission on the Future of Work, “Work for a Brighter Future,” January 22, 2019, https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/future-of-work/publications/WCMS_662539/lang--en/index.htm).

17. European Commission and Bocconi University, The Role and Impact of Labour Taxation Policies (Milan: Bocconi University, Center for Research on the Public Sector, 2011), https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=7404&langId=en.

18. See, for example, the work of the European Economic Area and Norway Grants Fund for Youth Employment, https://eeagrants.org/What-we-do/The-EEA-and-Norway-Grants-Fund-for-Youth-Employment.

19. Charles Grant, Sophia Besch, Ian Bond, Agata Gostyńska-Jakubowska, Camino Mortera-Martinez, Christian Odendahl, John Springford, and Simon Tilford, “Relaunching the EU,” Center for European Reform, November 2017, https://www.cer.eu/publications/archive/report/2017/relaunching-eu.

20. The digital economy is growing seven times faster than the rest of the economy, with investments in ICT accounting for half of European productivity growth (see European Commission, The Digital Economy and Society Index, 2018, https://europa.eu/european-union/topics/digital-economy-society_en and https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/desi).)

21. Luke Field, “A User’s Guide to the Citizens’ Assembly,” RTE News, January 11, 2018, https://www.rte.ie/eile/brainstorm/2018/0104/930996-a-users-guide-to-the-citizens-assembly/.

22. “Data Suggests Surprising Shift: Duopoly Not All-Powerful,” eMarketer, March 19, 2018, https://www.emarketer.com/content/google-and-facebook-s-digital-dominance-fading-as-rivals-share-grows.

23. Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, David A. L. Levy, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2017 (Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2017).

24. EACEA National Policies Platform, “6.8 Media Literacy and Safe Use of New Media,” European Commission, December 2018, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/en/content/youthwiki/68-media-literacy-and-safe-use-new-media-latvia.

25. Act to Improve Enforcement of the Law in Social Networks,” The Bunderstag, July 2017, https://www.bmjv.de/SharedDocs/Gesetzgebungsverfahren/Dokumente/NetzDG_engl.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2.

26. “France Passes Controversial ‘Fake News’ Law,” Euronews, November 22, 2018, https://www.euronews.com/2018/11/22/france-passes-controversial-fake-news-law.

27. “Action Plan Against Disinformation,” European Commission, December 5, 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/eu-communication-disinformation-euco-05122018_en.pdf.

28. “Code of Practice on Disinformation,” European Commission, September 26, 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/code-practice-disinformation.

29. “Final Report of the High Level Expert Group on Fake News and Online Disinformation,” European Commission, March 12, 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/final-report-high-level-expert-group-fake-news-and-online-disinformation.

30. Klára Votavová and Jakub Janda, Making Online Platforms Responsible for News Content (Prague: European Values Think-Tank, 2017).

31. “Germany: Flawed Social Media Law,” Human Rights Watch, February 14, 2018, https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/02/14/germany-flawed-social-media-law.

32. “Review of Cyber Hygiene Practices,” European Union Agency for Network and Information Security (ENISA), December 2016, https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/cyber-hygiene.

33. “Cybersecurity: Paris Call of 12 November 2018 for Trust and Security in Cyberspace,” France Diplomatie press release, November 2018, https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/french-foreign-policy/digital-diplomacy/france-and-cyber-security/article/cybersecurity-paris-call-of-12-november-2018-for-trust-and-security-in.

34. The European Parliament and The Council of the European Union, “Directive Concerning Measures for a High Common Level of Security of Network and Information Systems Across the Union,” Official Journal of the European Union, July 6, 2016, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016L1148&from=EN.

35. Better Internet for Kids, “European Cybersecurity Month—European Teachers ‘Get Cyber Skilled’,” September 28, 2018, https://www.betterinternetforkids.eu/web/portal/practice/awareness/detail?articleId=3574321.

36. European Parliament Resolution of 16 February 2017 With Recommendations to the Commission on Civil Law Rules on Robotics,” European Parliament, February 16, 2017,http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?type=TA&reference=P8-TA-2017-0051&language=EN&ring=A8-2017-0005; https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2018%3A237%3AFIN.

37. “Draft Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI,” European Commission, December 18, 2018,https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/draft-ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai.

38. Kati Van de Velde and Dirk Holemans, “Citizens Building a New Europe,” Green European Foundation, June 5, 2017, https://gef.eu/publication/citizens-building-new-europe/.

39. “Citizens Own One Third of German Renewables Capacity,” Clean Energy Wire, February 2, 2018, https://www.cleanenergywire.org/news/coalition-transport-agreement-citizens-own-one-third-renewables/citizens-own-one-third-german-renewables-capacity.

40. Fearless Cities is a global municipalist movement that seeks to defend human rights, democracy, and the common good (see http://fearlesscities.com/en/about-fearless-cities).

Establish a special commission on post-growth futures in the European Parliament.

Establish a special commission on post-growth futures in the European Parliament.

Set quality standards for online learning through pan-European accreditation and certification systems. This will enable people to continually improve their skills—a key requirement of the likely future labor market—and will build trust in this form of education.

Set quality standards for online learning through pan-European accreditation and certification systems. This will enable people to continually improve their skills—a key requirement of the likely future labor market—and will build trust in this form of education.

Dig into the sources of disinformation by conducting an in-depth analysis of the link between the platforms’ revenue models and the incentives to spread disinformation.

Dig into the sources of disinformation by conducting an in-depth analysis of the link between the platforms’ revenue models and the incentives to spread disinformation.